Take a Walk

A Quest into the Wild

Mount Parnassus (13,574′) and Bard Peak (13,641′) from Herman Gulch Trailhead

Introduction

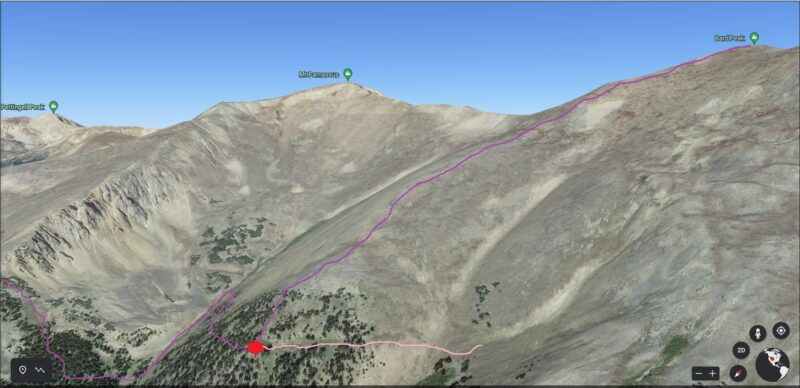

Numerous trip reports exist on climbing the 13ers in this range; however, there appears to be a need for a more detailed description of this particular route of climbing Parnassus from Herman Gulch Trailhead via Watrous Gulch Trail to Woods Mountain Ridge trail to a bushwhack up to Parnassus, hike the ridge over to Bard, bushwhack south from Bard to connect with Bard Creek Trail which takes us back to Watrous Gulch trail and then back to Herman Gulch Trailhead. Most of this is pretty obvious, except the descent from Bard. So, we’ll go quickly through most of this, but focus on that aspect of the hike.

Part 1

First things first. Herman Gulch Trailhead is close-ish to Denver, and thus, can be very busy. However, it is a nice trailhead with Port-o-Potties and nice parking just off I-70. From the trailhead you are on the CDT: Herman Gulch Trail very briefly before turning right onto Watrous Gulch Trail; there are signs here, the trail is large and well maintained, and it is obvious. You continue on Watrous for about 1.25 miles before reaching the Woods Mountain Ridge trail and veering sharply uphill to the right — towards an obvious saddle. It is a beautiful hike on a very well maintained trail and it has a little creek crossing with gorgeous views of the Front Range.

As you climb up the Woods Mountain Ridge trail you get some very nice views of Grays and Torreys, and we could even see the trail leading up to Grays’ summit. It is a splendid hike and there was still a nice trail that was never smaller than single track — it was pretty steep.

Saddle to Parnassus

Anyways, once you reach the saddle, if you look to your left (climbers left as you reach the saddle) you will see a trail leading up to Woods Mountain (a 12er) and if you look to your right, you will see a large climb with no clear trail (see second picture below). You want to turn right and climb up to Parnassus.

Once you get up this beast, you are pretty much there. It isn’t really a false summit, per se. From here, the next route is more or less obvious (depending on conditions). You do have two options, though, on how you want to tackle Bard. You can maintain the ridge proper (which is what most people do), or you could stay a little lower and traverse around and then come up a saddle on the opposite side of Bard. If you take the second option, which isn’t as steep and is probably easier, then you do add some distance since you have to turn left once you reach the saddle and then gain the summit of Bard. Either way, there isn’t anything special to know, other than that the ridge can hold snow which can make this treacherous. There are some trails on the ridge, but they fade and you really can’t follow one trail across the whole ridge — so just pick a line and stick to it.

Parnassus to Bard

The ridge hike, as we mentioned above, isn’t that bad. And you’ll be at Bard in no time. Below are a couple shots of the hike.

You can see that there is a trail on parts of the ridge, and on other parts there is nothing. You can also see that even in July during a hot summer, there is some snow.

Choices Choices Choices…

Once you are on Bard, you have a few choices to make. Are you going to head north to Robeson and Engelmann or are you going to head back? If you are going to head back, then you have to decide if you are going to retrace your steps or if you are going to head south and try and connect with the Bard Creek Trail. We weren’t trying to nab any other 13ers, and we had seen other trip reports where the authors had climbed down Bard and connected with the Bard Creek Trail, which we thought looked nice. However, it wasn’t clear where to descend and what to shoot for, and this is where our trip report will focus some attention on our idea of how to do this. (I want to state, though, that the recommendation below is only if the conditions are similar to what we were hiking in — that is, relatively snow free.)

Bard Descent to Bard Creek Trail

First, looking south from Bard you are going to see a large ridge that connects to Parnassus to your right, a smaller ridge to the left of that with a gully/cirque between them; directly below, you will see another gully/cirque and another ridge to your left. Our recommendation is to head to that smaller ridge to your right — you can even take the ridge down from Bard a bit to meet up with it. Going straight down from Bard is not pleasant. It is steep, loose and uneven — and it is about 1,400 ft. of elevation loss before you reach the Bard Creek Trail. Below are some shots from Google Earth and from our hike that show what I’m talking about.

Bard Creek Trail does go up and over two ridges if you choose to go this way. So if you retrace your steps, you are going to regain Parnassus which is 600 ft. of elevation gain. But if you go down to Bard Creek Trail, you are going to have to do some route finding and still climb out. Up to you. But it is hard to see what you are supposed to do from this angle, so I got Google Earth out and took some screen shots of what we think is the best way down.

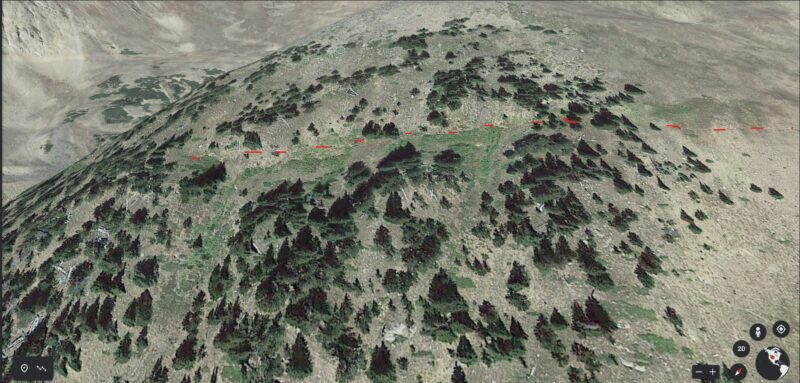

Bard Creek Trail to Watrous Gulch Trail

So, once you are down to the trail, you can relax a bit and then traverse around the ridge and down into the cirque/valley below. At this point, you again lose a trail, but you have cairns that do lead you in the right direction — which is just following the stream. (see below).

Eventually, you come to what looks like a camp site and just past that is a cairn that points into the trees. Take that path. From there, there is mostly a trail to the plateau.

Conclusion

All in all it was right at 9.5 miles for us and about 4,700 feet of elevation gain. As you can tell, depending on how you do this, your mileage and potentially elevation gain may be slightly different. I think this was a fun route and the descent from Bard made more of a challenge. But, it would have been nice to have better beta on this, so I hope this helps someone. I would like to one day do this again, and try the route we have proposed. If you try it out, let us know in the comments. Have fun out there and be safe.

Igloo Peak 13,060 ft. – Independence Pass

“It is not the mountain we conquer, but rather ourselves.”

Sir Edmund Hillary

Go Forth

Sometimes you just have to get out of the house, and yardwork just won’t cut it. Allyson and I headed up to the mountains with no real plans — only to get outside. We brought the tent and some supplies and we headed west. An initial idea was to go to Twin Lakes and find a campsite; but, alas, there were no campsites that we could see. The road kept on going and so we kept on following it. Eventually, we found ourselves on Independence Pass, which is the highest paved road in North America (or so I’m told).

We took a quick look around and noticed a trail that ran out towards some peaks off in the distance and our minds began thinking about whether we should head out on them. However, we didn’t have a campsite yet and so had no clue where we were sleeping. We ended up in Basalt, Colorado, and at dinner pulled up the forest services maps and found a promising site. Turned out that we lucked out and found a spot on a gnarly 4WD road. Below is the view from out campsite.

Decisions

We got up the next morning and found ourselves heading back towards Denver by way of Independence Pass. In our minds we thought we might run at McCullough Gulch or perhaps paddleboard on Twin Lakes. But when we came upon the pass again we saw the title image of this post. Perfect reflections of the mountains and sky in calm waters with a freshly dusted vista of mountains. We decided that we would just run here on the trail we saw yesterday and see where it goes.

As is becoming our modus operandi we didn’t know the names of the peaks or really even if they were named. Just that they were there and we felt called to them. So, we started jogging up the trail, and it was pleasant at first. The grade was modest and there were very few people on the trail despite a very busy parking lot. But, then the climb became steeper and the elevation more noticeable. I took some pictures (below) to catch my breath.

We’re Doing This

I don’t think we really had a good plan on where we were going. Were we just exploring? Were we trying to go to the middle peak? The farthest peak? No one knew. We just headed out on the trail and figured we couldn’t get lost. But after the climb up to the first summit we knew we were going to at least the middle peak, which we later learned was named Igloo Peak and was 13,060 ft. tall.

My lungs were on fire by the time we hit the steep climb up to that first summit, but we were feeling good overall. The mountains looked beautiful and the weather was cool — much better than the 100 degree weather we had a few weeks ago in Denver. There were a number of wildflowers out, mostly little blue groundcover and yellow alpine Avens, but some alpine clover and other species. Below are some images from the first section.

Igloo Peak

Eventually, we came to a rock tower and thought, does this go? And not only does it go, it has a trail along the backside. The trail was loose rock and scree, but a trail nonetheless. We continued on and found ourselves at the peak of Igloo. The trail, sadly, did appear to stop; or at the very least it became a tad sketchy. Later, I read that if you continue on the ridge proper to Mountain Boy it is a dangerous class 4 climb on loose rock — so I’m glad we turned back. There were other trails and we speculated, apparently correctly, that one could climb down and approach from lower down. Below are some images from the summit of Igloo and the rock tower with Allyson on the trail.

Heading Back

The jog/hike was a nice surprise; and we didn’t expect for the peak to have a name. But like most things in life, now we have even more to explore than we did before. If you go north from the Independence Pass TH there is another trail that goes to other 13ers; and we will have to come back for Mountain Boy, which we didn’t even know existed. And now we have seen Grizzly Peak (the tallest 13er at 13,988 ft.) and countless other 13ers. The area could provide weeks of exploration. Not only that…but we do have to go back and paddle Twin Lakes and explore the Independence ghost town.

So we headed back down and continued on our adventure. Overall the route is about 5 miles RT with maybe 1,300 ft. of elevation gain (or thereabouts). I’d say that over 90% of the trail is runnable, but that last section before Igloo is too loose (at least for me). Happy adventuring!

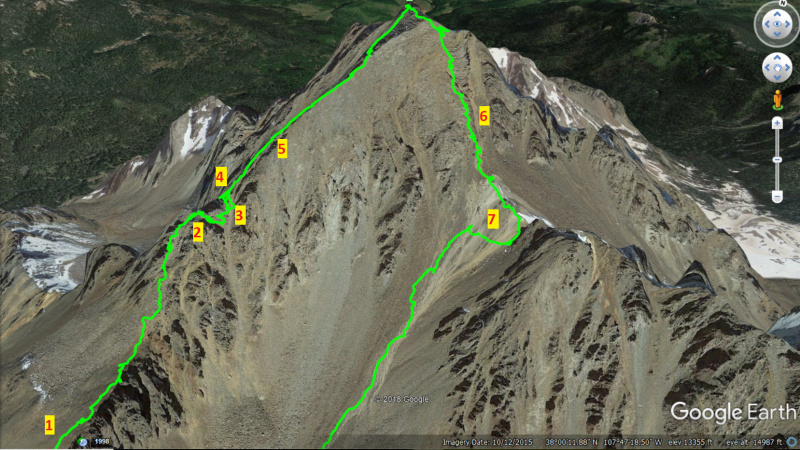

Mt. Sneffels via Southwest Ridge – Beta

This post is primarily a beta post for those interested in climbing Mt. Sneffels via the Southwest Ridge and descending the standard route (South Slopes). The approach is relatively straight forward and will not be discussed. The post is broken down into 7 sections; each section is numbered from the GPS image below.

Section 1

Turning right onto the ridge you see the Pinnacles; we also encountered a large snowfield with steep snow. Traction and an ice-axe are recommended. Crampons are overkill, but some people used them. This year (2019) was particularly snowy, and the mountains are holding lots of snow. In previous years, this area would not have required more than a helmet, but this year the snow posed some risk. A few images below give an idea of what it looked like.

Section 2 – 3

Once up the talus above the snowfield there is a path that appears to go left, however, this route does not go. Instead, veer right and downclimb an obvious trail that becomes loose and steep. Once down veer left and aim for the large gully ahead of you. This year, as mentioned earlier, left a lot of snow, and the gully was filled with snow. It was very steep and climbing on the snow felt risky; luckily, climbing up the left side of the gully allowed us to avoid the snow completely. After climbing up the gully cross to the notch seen in the pictures below.

Section 4

This felt like the crux to us. There is a notch you climb up with some vertical climbing which require some climbing moves. The rock was wet in areas and slick, which made it more difficult; however, it was very doable. I wouldn’t rate the moves as harder than VB or maybe an easy V1. Once up the two “bouldering” sections the climb becomes much easier. It is possible that there was an easier way up and we missed it, possibly to climbers left — we ended up climbing climbers right.

Section 5

Right after you see the “kissing camels” rock formation veer right. It is easy to miss this ramp out of the gully, see below.

Section 6

Once to the summit the way down is relatively obvious (although no true trail exists). Follow the ridge down the south slope veering left until you find the cairned v-notch. Downclimb the class 3 v-notch into a steep gully. Again, snow filled a large portion of the gully and traction and protection (ice-axe) were good to have. Allyson kick-stepped part of the steeper and slicker part of the gully. This is the last nasty snow section.

Section 7

Lastly, once to the saddle there is a trail that leads over a very small rock outcropping. If you follow this it leads to a cliff wall on the other side and goes down. However! The trail runs out and you are left on steep, very loose rock and dirt. The better option is to not even cross the saddle and stay down-climbers right. This gully is insanely slick in the middle and very steep; it was incredibly difficult to traverse over to the right side of the gully. Once on the correct path, it was steep and loose, but very doable. It was our least favorite part of the hike.

Conclusions

Mt. Sneffels was one of the most beautiful climbs and basins we have been in to date. But it does pose a few dangers. Even if the snow hadn’t been crazy this year, rockfall is still an issue. Helmets are a must, especially for the south slopes where there were far more climbers. We heard a large rockfall and climbers screaming rock from a distance on the south slopes. I would encourage climbers to wear a good helmet on these routes.

The southwest ridge was fun, but it was a true class 3 climb with some good exposure. It would not be a great first class 3 due to the creativity needed to navigate some of the terrain (such as around snow, etc.). The hike itself, though, is not long, and it is very fun.

Happy Trails!!

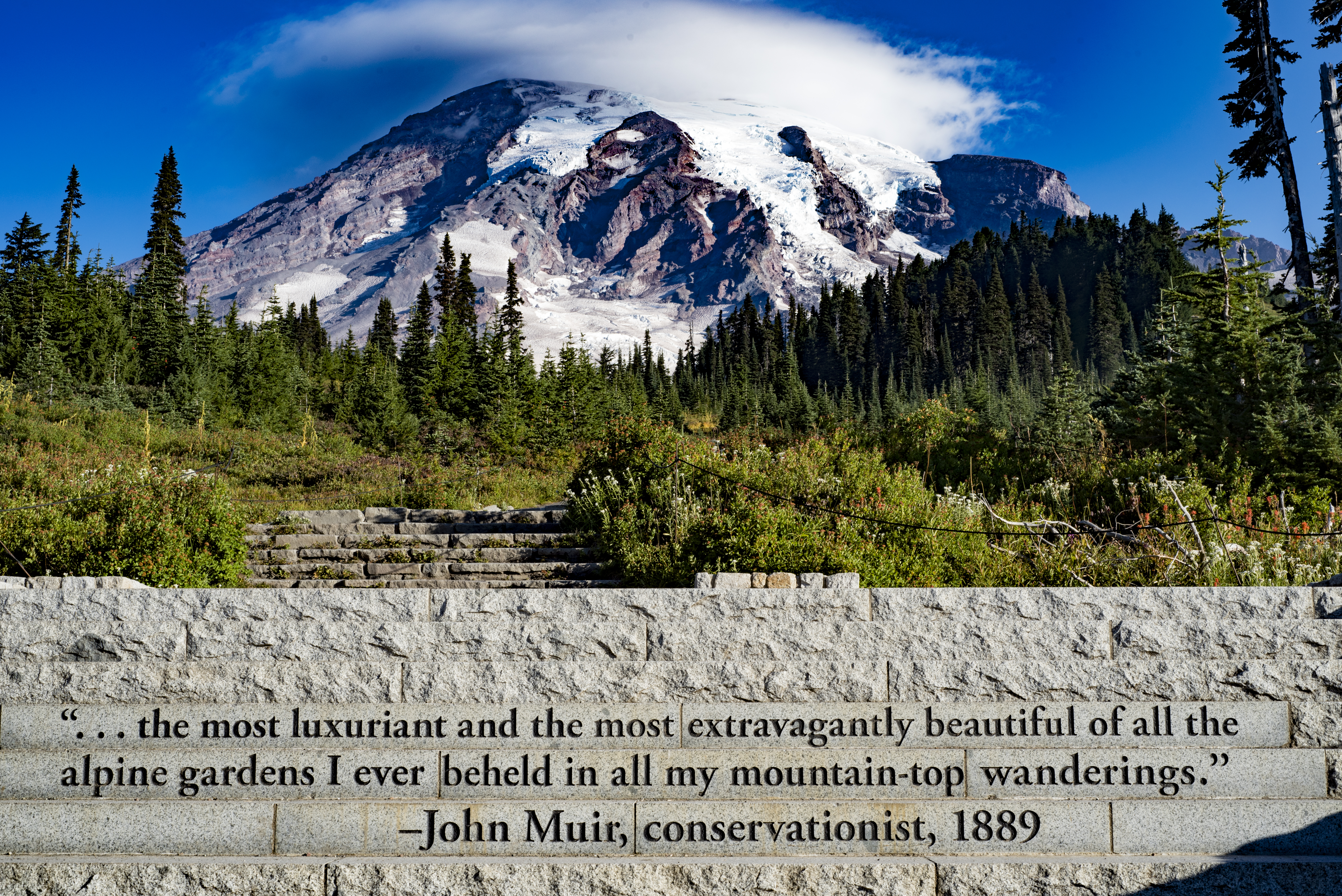

Camp Muir, Mount Rainier 10,100 ft

Some Background and History

A rich geological and human history both contribute to the wonder of the stratovolacano that is Mount Rainer. The peak was forged by fire and years of lava, ash, and pumice piling up, layer upon layer, eventually forming a summit cone, a consequence of thousands of years of volcanic activity. Close to 6,000 years ago, the peak had a violent eruption which knocked off the cone, and subsuquent years of volcanic activity left the peak with two overlapping craters at the top. It is the largest peak in the Cascade Range and sits prominently above all other peaks in the nearby vicinity at a stunning 14,411 feet above sea level. For perspective, the others sit around 6,000 feet. The mountain face is constantly changing as fluctuations in the weather and temperature shift and melt its heavily glaciated regions. Every few hundred years, small to moderate eruptions occur, with the most recent occuring in 1894. Importantly, the mountain is still an active volcano.

The Mount Rainier region has always pulled humanity close, providing natural resources and in more modern times, recreational ones. Native American tribes have gathered for millenia to hunt and gather resources here. The first recorded ascent occured in 1870 by Rhode Islander, Hazard Stevens. The park was established in 1899, and the true infrastructure began to take shape following the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, though the road to Paradise had been in place since 1910. There has been some tumultuous history of the park through the years, that we won’t go into here, but relative stabilty has been achieved since the 1960s. Visitation continues to boom, with 1.8 million visits recorded in 2016. The number of attempted climbs of Mount Rainier is also large. In the last 8 years, there have been between 10,000 and 11,000 yearly registered climbers.

Our Trip

We have not escaped the allure of Mount Rainier and decided to plan a visit to the mountain in mid-September as part of a week long excursion to the Pacific Northwest. Though we did not decide to make an attempt at the summit as we had insufficient time to secure guiding resources, we did want to go halfway and visit the famous Camp Muir. Camp Muir, named after the famous alpinist, is nestled at 10,100 feet above the Muir Snowfield and on the edge of the Cowlitz Glacier and serves as base-camp for those planning a summit attempt. Reaching the camp requires a mix of trail hiking and traversing the unmarked Muir Snowfield. The one way trip is roughly 4.5 miles with close to 4,800 feet of elevation gain from the Paradise Visitor Center. The National Park Service recommends the trip for only experienced hikers as there is no marked path up the 2.2 miles of the snowfield and white-outs are frequent.

Skyline Trail

On September 6th, we flew in to Sea-Tac and immediately drove down to our quaint cabin nestled in the woods approximately two miles from the park entrance. After a good night’s rest, we arose at dawn and made the short drive into the park to the Paradise Hiker’s parking lot. Blue, clear skies were abundant, and we began our journey on the Skyline Trail. The trail is an extremely steep and well-paved path for the first 10-15 minutes of hiking before it turns into a much more pleasant gravel/dirt path. There were several signs along the way to direct us to the direction of Camp Muir on this portion of the hike as many side trails exist to gain different vantage points of the the nearby glaciers and the mountain. Near mile 1.1, there was a junction in which both routes go the correct direction. Going left leads to Glacier Vista, overlooking the Nisqually Glacier to the west which also has a waterfall. Going right bypasses the ridgetop and takes hikers on a more direct route. Of note, the trails do reconnect fairly quickly. On the way up, we bypassed the overlook and continued toward our objective. At approximately 1.6 miles, we saw the sign for Pebble Creek and followed it to the creek at about 2.1 miles. We climbed over the creek and past McClure rock. Looking down at our GPS, we noted an elevation of about 7,300 feet. The trail had now ended. It was time to throw on the spikes. We entered the snow.

Muir Snowfield

Our spikes grabbed the snow easily, and we proceeded upward and closer to the upper reaches of Mount Rainier. We took the most obvious path forward and kept near earlier bootpack and some glissading paths. Camp Muir was not yet visible. The snowfield appeared to stretch for miles and miles. Intermittently, there were some brief breaks in the snow via small sections of rocky outcroppings. We used one once to sit and dress a blister since it was preferable to sitting in wet snow. The snow was a strange redish muddy color in places. We’ve been told this is common in late summer due to pumice and ash. At 8,600 feet, we noted the turn off for the ridge that connects to Anvil Rock, a 9,000 something foot detour on the way to Camp Muir. We had our goal in site and did not choose to venture on this scenic path this time around. In the remaining mile on the snowfield, we acsended roughly 1,500 feet. It was intense. We kept checking the GPS thinking that it must be off or something. Surely we are higher in elevation with only a mile to go we thought. There were several wire wands in the snow with florescent tape marking the best path forward, which was helpful considering a few crevasses had started opening up on the snowfield. One we noted was 3 feet wide in places. Camp Muir and the snowfield are nearly completely surrounded by glaciers, and there are several warning in place by the National Park Service reminding hikers and climbers of the dangers of climbing the snowfield. Sadly, this hike has claimed a few lives when conditions turned poor. Backpacker magazine ranks the hike as one of the 10 most dangerous in America.

Camp Muir / Cloud Camp

Camp Muir was originally called Cloud camp, and aptly so. The small camp sits above the Muir snowfield on the edge of the Cowlitz Glacier seemingly floating above the world below. After John Muir made the 6th recorded ascent in 1888, the name of the camp changed. Excitement ensued as we began to get our first glances of the camp. The first structure that camp into view was actually the guide hut. Only the famous stone structures would come into focus as we got much closer. We followed the boot pack and continued upward. It was a bit farther than it looked. The blue tint of the glaciers were quite apparent now, and finally we touched of our feet on hard rocky surface. We had made it to Camp Muir. While we were only sitting slightly above 10,000 feet, the hike was not too unlike many of our treks up to 14,000 feet. The elevation gain was intense. The camp was full of life and busy just before noon on a pleasant Friday. There were several guide groups and camps already set up on the Cowlitz glacier. Half a dozen or so day hikers were already perched at the front of the stone sleep shelter. We spent almost 45 minutes at the camp, eating some food and relaxing in the beauty of our surroundings. It was interesting to see tents pitched on the edge of 6 foot wide crevasses on Cowlitz Glacier. There were several warning signs in place stating that unropped travel past this point was not advised. As we looked south, we could see very clearly Mount Adams and Mount St. Helens. Mount Hood was slighlty visible between these two mountains.

The Descent

It was finally time to return to the world below, and we reluctantly put our spikes back on and began our descent. It was afternoon now, and the snow had gotten quiet slushy. Even in spikes, we were slipping and sliding. We eventually determined that the most efficient route down the mountain was via running/sliding down the mushy snow in our boots. There were several glissading paths that we saw on the way down, but at this point, unless they were steep, it was very hard to gain any speed. Scarily, we noted that one glissade path led straight into a crevasse. Though it was only 1 to 2 feet wide, it was still a scary prospect to think that a joyous slide might land you in a deep ice pit. On the way down, we saw several guide-led groups heading up to Camp Muir for a night’s rest prior to the summit push. Many of them looked a bit miserable to be honest. Though one day, we may be returning and participating in that march, today we were free to frolick down the mountain. On the final section of steep snow before reaching Pebble Creek, there was a short but very steep glissade. Several groups gathered here, and we all took turns gleefully sliding down it. There was even a bump that allowed those of us with enough speed to catch some air. Pure Joy.

Paradise Mount Rainier

Once on dry, snow free ground we took our time enjoying the Skyline Trail. We took the loop that looks directly over the Nisqually Glacier this time. There were now hundreds of people out on the trail enjoying the bluebird day and exquisite surroundings. We returned to the Paradise Visitor Center and enjoyed the small but interesting display they had on the stratovolcano and then determined it was time for some real food and a soak in the hot tub at our Cabin. On the drive out of the park, we made one extra stop at Narada Falls for some beautiful waterfall pictures. This requires just a short hike down a steep path.

Parting Thoughts

The hike to Camp Muir was strenuous but rewarding and fun. The scenary was breathtaking virtually the entire hike. Prospective hikers to Camp Muir should remember that part of the trail is on a long snowfield covering nearly 2.2 miles and very steep at portions. While we had a safe fun day, weather can and does often deteriorate quickly and can turn the snowfield to a blanket of white leaving hikers with no sense of direction. This is particularing harrowing here, because there are cliffs and crevasses surrounding the snowfield. Compass/map and GPS are critical for this trek.

Side notes: Verizon had some cell reception at Camp Muir and a bit near Pebble Creek. AT&T had none…anywhere. Also there is a cafeteria at the Paradise Visitor Center. We got small snacks here and they were tasty but expensive. We ask the cashier why the prices are so high. He replied ” that’s the high altitude tax” of which we replied “hey man, this is the elevation of our living room!” To put things in perspective, Paradise is only 5,400 feet above sea level, close to that of our home in the Mile High City. Sigh. Everything is relative. And lastly, eat dinner at Copper Creek Inn Restaurant right outside the park. It was amazing!